How do you approach research methodologies for academic journey?

Lecture: Martin Hosken.

Write your own definition of the word ‘research’:

‘A cognitive process of responding to and applying various forms of information‘.

Is research a science, an artor even a craft? Do you consider it primarily an academic exerciser is it an activity of life? Apart from this course, when was the last time you had to engage in what you would term ‘research’?

In my role as a junior designer I actively engage in technical research to improve my design skillset and research process driven methodologies to improve my application of professional practice. However outside of work and academia research is still a prevalent active and perhaps subconscious process inherent to human experience and daily life; for instance I consider finding directions to a new place, learn about the requirements of my pets forms of information gathering and applying. Therefore in response to the question of the nature of research, I feel that it can be all, science, art and craft as it is a broad universally applicable process.

Stop the presentation and spend 10 –15 minutes looking around the room that you are now sitting in. Become curious about its nature.

Are there any traces of a previous occupant? What happens if you rearrange the furniture? How would the atmosphere change if you repainted the room blue, white or purple? Do you feel cosy or cramped? Why did the electrician place the light in the centre of the room? What if the window was smaller or bigger? Play with your imagination.

In my office room overlooking my garden and the surrounding woodland I feel happy and safe, but also feel a longing to be outside in nature. The windows are quite large enough to feel connected to the natural world, however if they were smaller I would feel the rental houses magnolia walls closing in on me and feel resentful. If they were bigger I would consider this room to be designed in alignment with a biophilic design philosophy which would make me happy. On this note, if the room were painted a light blue or green I would be relaxed and content, but if it was dark it would cancel out the limited sunlight from bathing the small room so I might feel trapped and claustrophobic. Although I love my houses quirky features such as original old oak doors and 1970s art deco revival ceramic fireplace, some evidence of previous occupancy such as patterned ceiling wall paper which I’m not allowed to change under the rental agreement, make me feel like I’m in someone else’s shell.

Etymology

‘research’,derives originally from the French “to closely search”, which has its root in the Latin circare–literally to go about, to wander.

‘Circareis also of the same root as the words circle and circus. In playing with the images that emerge from etymology, we allow our own imagination to play. In the case of the word research, we have encountered such terms as seeking, searching, to wander through in a circular type motion. It is this sense of freedom that I am very keen to evoke.’

Philosophy: how is knowledge arrived at

experience and questioning of experience – reflectivity

Rationalism vs Empiricism

The rationalists claimed the ultimate starting point of all knowledge is not the senses, but reason. They maintain that without prior categories and principals supplied by reason, we couldn’t organise and interpret our sense experience in any way. Rationalism in its purest form goes as far as to hold that all our rational beliefs and the entirety of humanknowledge consist first in principles and innate concepts that we are just born having, that are certified by reason along with anything logically deduced from these first principles.

However, in direct opposition, the empiricists claimed that sense experience is the ultimate starting point for all our knowledge. The senses, they maintain, give us all our raw data about the worldand without this raw material, there would be no knowledge at all. Perception starts a process from which comes all our beliefs. In its purest form, empiricism holds that sense experience alone gives birth to all our beliefs and all our knowledge.

Throughout the centuries,our cultures have developed alongside this philosophical journey that has replaced the theological doctrine centred upon God, with a philosophical doctrine centred upon man. Until today we can broadly identify four key concerns that underpin our philosophical categorisations.

Metaphysics asks questions around our ultimate sense of reality. It deals with ontology, the nature of being. In this way, it asks the big questions–man, God, what’s it all about, and can there ever be an objective truth?

Aesthetics asks questions of the nature of beauty. It dealswith judgement and perception, order and proportion.

Ethics asks questions of how we should conduct ourselves. It explores ideas of morality, judgement and importantly, the desired or appropriate relationship between the individual and the state.

And finally, epistemology, which engages the theory of knowledge itself, especially with regards to its origins, methods, validity, limits and scope, and the distinction between justified belief and opinion. Epistemology investigates the nature of human knowledge and is of much concern when we start to approach the methodologies and research.

Methodology a branch of knowledge that deals with the general principles or axioms of the generation of knowledge. A methodology describes the overall justification or epistemological approach that you are taking towards your studies. It refers to the rationale and the philosophical assumptions that underlie any natural, social or human science study. our methodology is in effect the pillar of knowledge that you are standing upon. You may ask yourself, from where do you affirm your approach? What arena of knowledge underpins your approach?

A method refers to the process used to collect information and data for the purpose of analysis, enquiry or decision making. In other words, the method refers to the different techniques a researcher employs in order to construct data and interrogate the sources.

A qualitative approach is broadly concerning discourse and language, while a quantitative approach broadly concerns measurement and numbers.

Research principles:

- minimise the risk of harm

- obtaining informed consent

- protecting anonymity and confidentiality

- avoiding deceptive practices

- providing the right to withdraw

Covert research: if we are to extend knowledge, then deception is sometimes a necessary component of covert research, which can be justified in some cases.

A Primary Source provides direct or first-hand evidence about an event, object, person or a work of art. Primary sources include historical and legal documents, eye witness accounts, results of experiments, statistical data, pieces of creative writing, audio and video recordings, speeches and art objects.

Secondary source of information is one that was created later by someone that did not experience first-hand, nor participate in the events or conditions being researched. For the purpose of an historical research project, secondary sources are generally scholarly books and articles.

Analysis: formal or contextual. A formal analysis refers to a direct description of what the individual has done and how they have done it–it is in this way simply a description of the item. While a contextual analysis unpacks the wider context surrounding the object of investigation and how the particular item may fit into, or impact upon the world around it.

Laurel, B. (Ed) (2003) Design Research: Methods and Perspectives (Links to an external site.). Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Collins, H. (2010) Creative Research; The Theory & Practice of Research for the Creative Industries (Links to an external site.). Lausanne: AVA Publishing.

Bestley, R. Noble, I. (2016) Visual Research: An Introduction to Research Methods in Graphic Design (Links to an external site.). London: Bloomsbury.

What makes a good research question?

1.A good research question must be relevant i.e. it arises from issues raised in literature and/or practice, and the questions will be of academic and intellectual interest.

2.A good research question is manageable. You must be able to access your sources of data be they documents or people or objects, and to give a full and nuanced answer to your question.

3.A good research question is substantial and original. The question should showcase your imaginative abilities, however far it may be couched in existing literature.

4.A good research question must be fit for assessment. Remember, you must satisfy the learning outcomes of your particular course. Your question must be open to assessment as well as interesting. It must also be clear and simple. Your question maybe come more complex as your research progresses, but start with an uncluttered question and then unpeel the layers in your reading and writing.

5.Aresearch question needs to be interesting. Try to avoid questions which are too convenient or flashy. Remember, you will be thinking about this question for most of your course.

Literature Review

When assessing the relevance of such sources, a useful consideration is what is called the CRAAP test.

- C= currency. Is the information up to date? Does this matter?

- R = relevance. Does it relate well to your research area?

- A = authority. Who is the author or source? Are they credible?

- A= accuracy. Is it reliable, truthful and correct?

- P = ourpose. What is the reason it exists? Or who is it aimed at?

Ideas Wall:

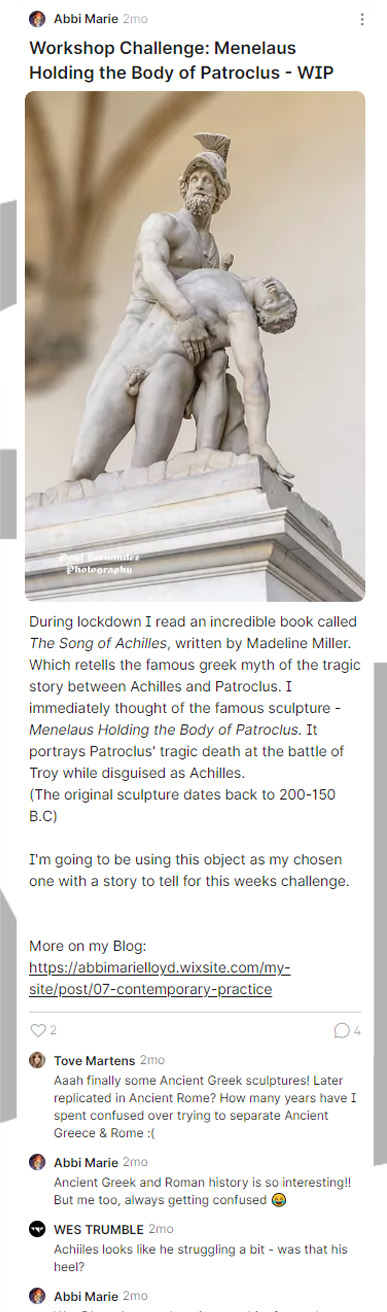

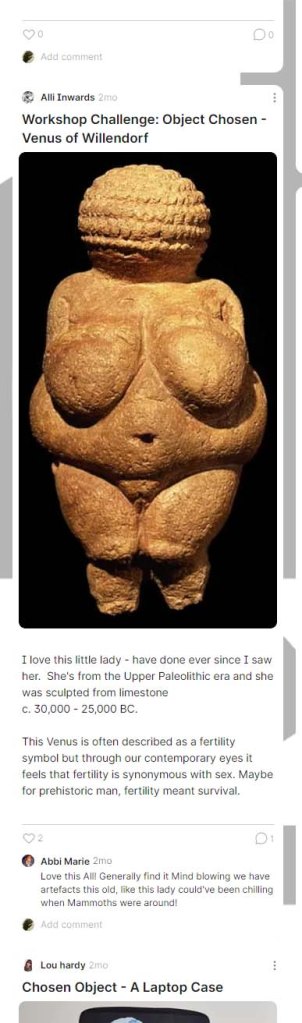

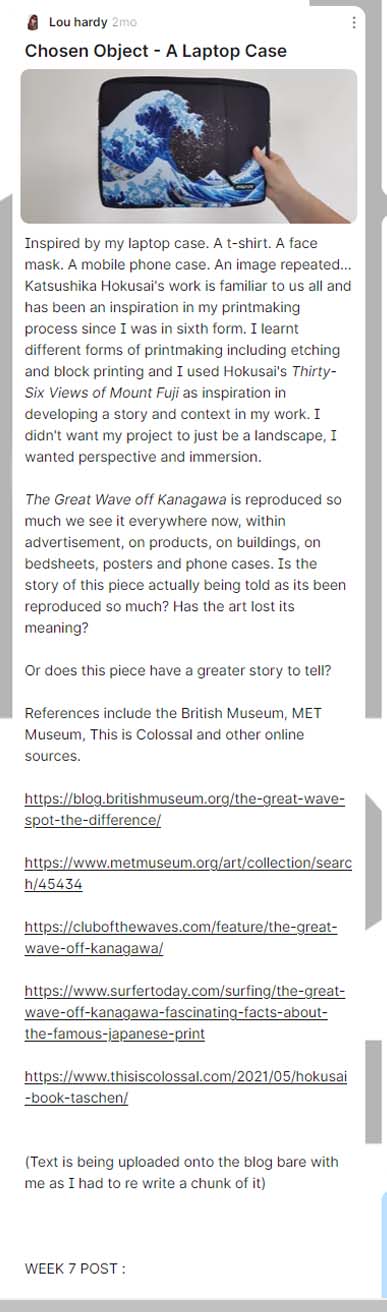

Workshop Challenge

How do you approach research methodologies for your academic journey? Select and deploy appropriate research methodologies to inform a need within a project.

- Choose an object you feel has a story to reveal.

- Write a 300 word text acknowledging the texts that link to your writing.

- Upload an image of object with the title of your written precis onto the ideas wall.

- Upload a link to your blog onto the ideas wall, with your image and your 300 word referenced precis, and demonstrating your reflection.

As my fine art practice has been largely influenced my nature and ephemerality, I have always been inspired by natural artefacts found in the landscape such as stones and animal bones. Initially I was quite overwhelmed by the openness of this brief, however the plethora of historical, archaeological and religious lines of enquiry on the ideas wall, in contrast with familiar domestic objects such as Shiina’s rubber duck and Lou’s laptop bag inspired me to reflect on the relationship between history, spirituality and contemporary culture.

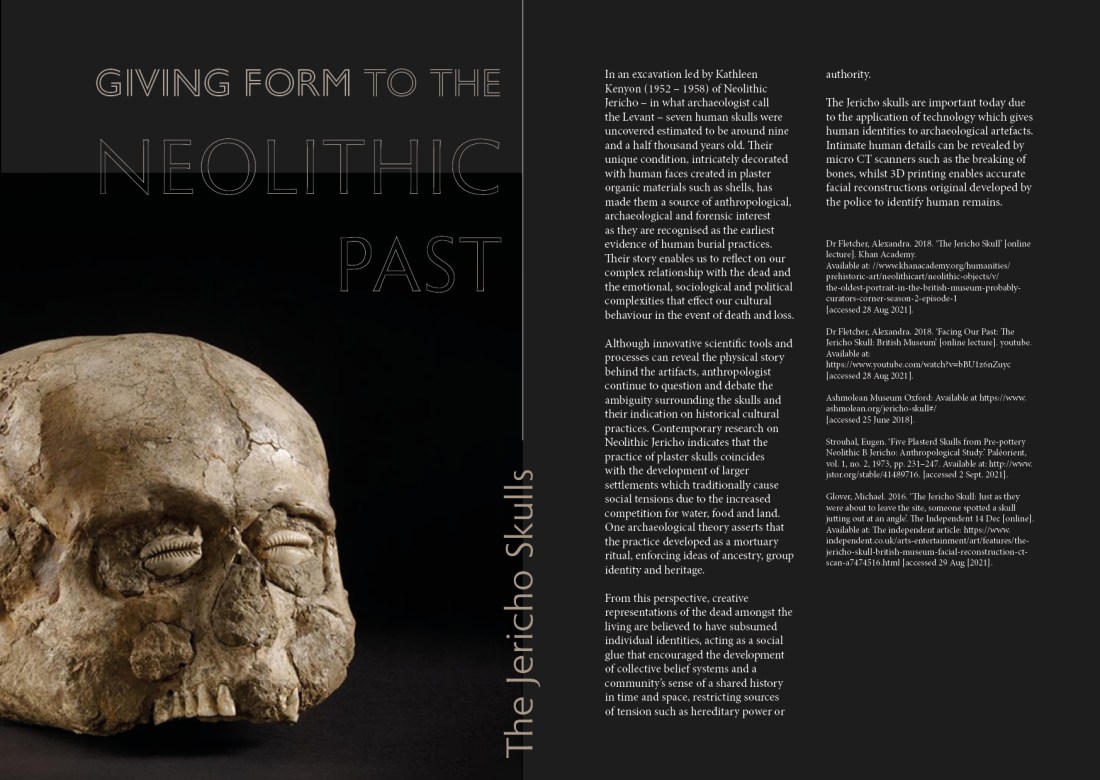

Sheep Skull found in the Wastwater Fells, Lake District.

Considering themes of environmentalism and ethics explored in my own practice during this module, the skull evokes potential research questions regarding the effect of animal agriculture on the landscape, climate change and the practice of rewilding. This thread of research could be explored through a range of philosophical, ethical and scientific methodologies informed by a range of qualitative and quantitative data. However, the ideas wall provoked further questions and a sense of discipline when reflecting on the object itself and its broader story within ancient contemporary contexts. Therefore I became interested in skulls as historical and archaeological artefacts and their implications on religious ritual in ancient culture.

Own Research

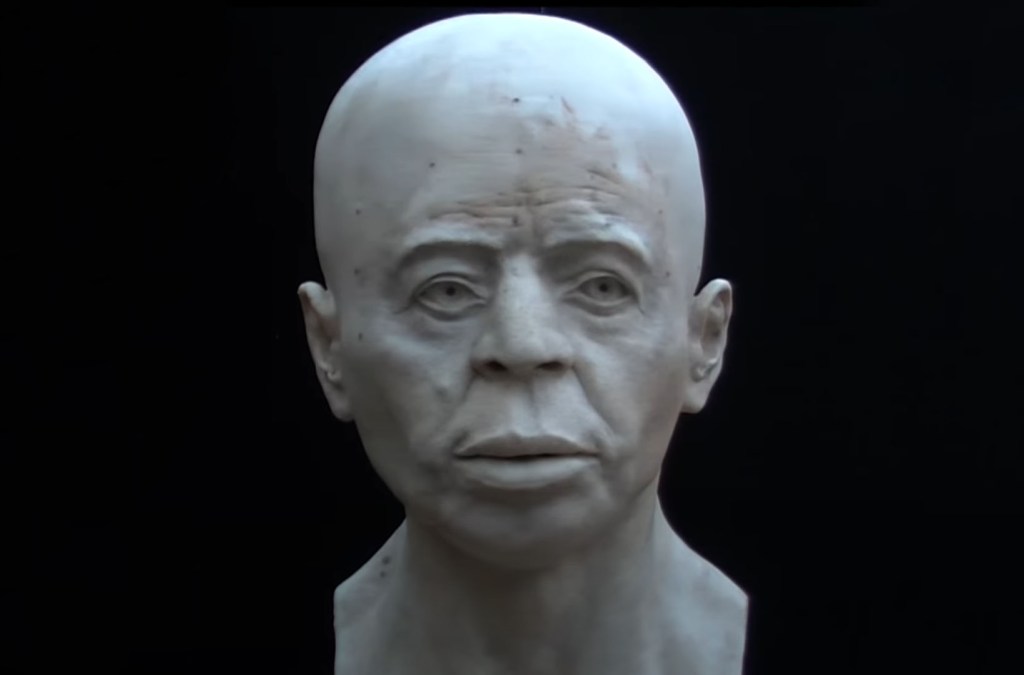

Forensic reconstruction and scientific applications

Methodology

Jericho skulls fascinate me as although they inform us on the cultural practices and historical context of the Neolithic period, there is still ambiguity and academic debate surrounding their purpose as a creative burial practice. The story behind the plaster skulls enables us to reflect on our complex relationship with the dead and the emotional, sociological and political complexities that effect our cultural behaviour in the event of death. My analysis of plaster skulls will adopt an anthropological methodology, using archaeological sources to decipher the cultural narrative behind their existence. In addition to this, I will also explore technological and scientific methods that have been applied to the research of the artefacts in order to uncover information of cultural resonance today.

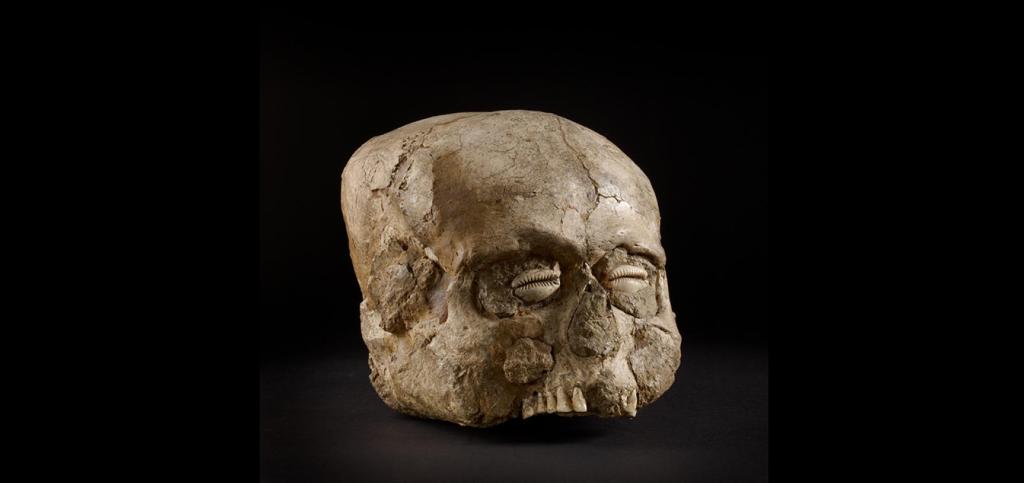

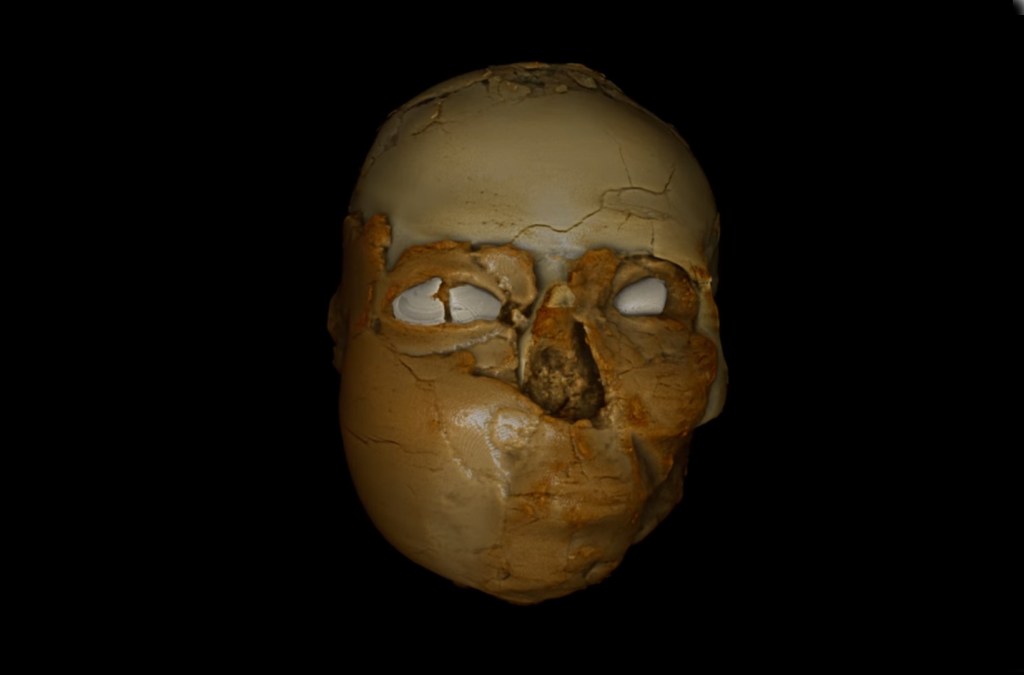

300 Word Written Precis

In an excavation led by Kathleen Kenyon (1952 – 1958) of Neolithic Jericho – in what archaeologist call the Levant – seven human skulls were uncovered estimated to be around nine and a half thousand years old. Their unique condition, intricately decorated with human faces created in plaster organic materials such as shells, has made them a source of anthropological, archaeological and forensic interest as they are recognised as the earliest evidence of human burial practices. Their story enables us to reflect on our complex relationship with the dead and the emotional, sociological and political complexities that effect our cultural behaviour in the event of death and loss.

Although innovative scientific tools and processes can reveal the physical story behind the artifacts, anthropologist continue to question and debate the ambiguity surrounding the skulls and their indication on historical cultural practices. Contemporary research on Neolithic Jericho indicates that the practice of plaster skulls coincides with the development of larger settlements which traditionally cause social tensions due to the increased competition for water, food and land. One archaeological theory asserts that the practice developed as a mortuary ritual, enforcing ideas of ancestry, group identity and heritage.

From this perspective, creative representations of the dead amongst the living are believed to have subsumed individual identities, acting as a social glue that encouraged the development of collective belief systems and a community’s sense of a shared history in time and space, restricting sources of tension such as hereditary power or authority.

The Jericho skulls are important today due to the application of technology which gives human identities to archaeological artefacts. Intimate human details can be revealed by micro CT scanners such as the breaking of bones, whilst 3D printing enables accurate facial reconstructions original developed by the police to identify human remains.

References

Dr Fletcher, Alexandra. 2018. ‘The Jericho Skull’ [online lecture]. Khan Academy.

Available at: //www.khanacademy.org/humanities/prehistoric-art/neolithicart/neolithic-objects/v/the-oldest-portrait-in-the-british-museum-probably-curators-corner-season-2-episode-1

[accessed 28 Aug 2021].

Dr Fletcher, Alexandra. 2018. ‘Facing Our Past: The Jericho Skull: British Museum’ [online lecture]. youtube.

Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBU1z6nZuyc

[accessed 28 Aug 2021].

Ashmolean Museum Oxford: Available at https://www.ashmolean.org/jericho-skull#/

[accessed 25 June 2018].

Strouhal, Eugen. ‘Five Plasterd Skulls from Pre-pottery Neolithic B Jericho: Anthropological Study.’ Paléorient, vol. 1, no. 2, 1973, pp. 231–247. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41489716. [accessed 2 Sept. 2021].

Glover, Michael. 2016. ‘The Jericho Skull: Just as they were about to leave the site, someone spotted a skull jutting out at an angle’. The Independent 14 Dec [online]. Available at: The independent article: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/the-jericho-skull-british-museum-facial-reconstruction-ct-scan-a7474516.html [accessed 29 Aug [2021].

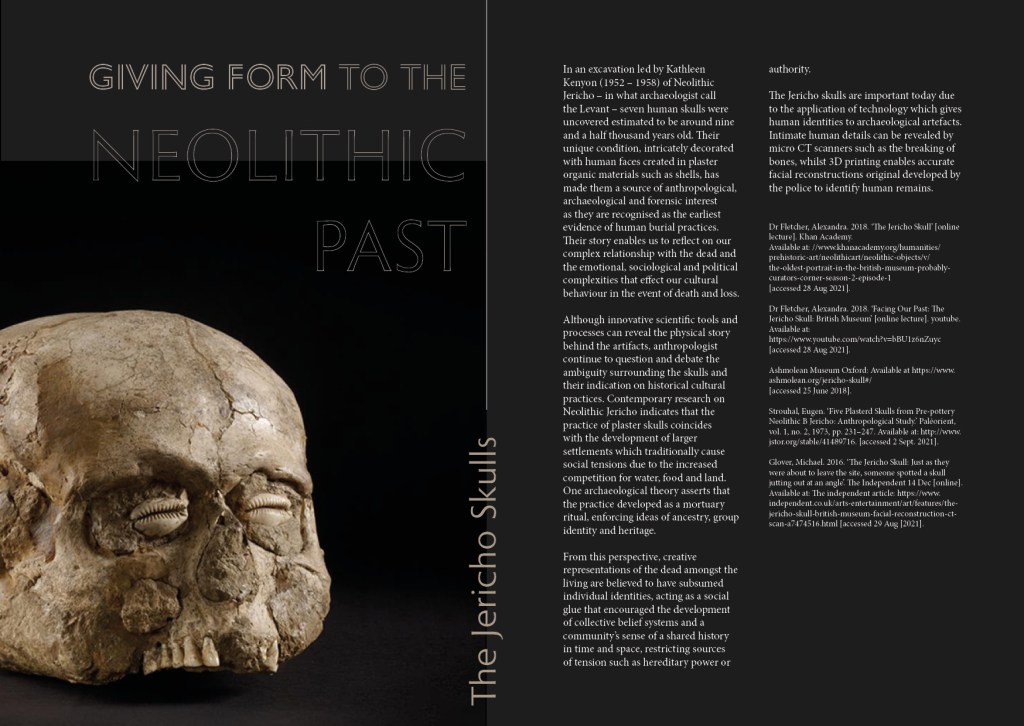

Editorial Design: Process

Final Outcome

For this project I wanted to create a final editorial design reflecting the simplicity of academic publications, such as exhibition catalogues or museum leaflets. In this piece I used a colour palette based on the original photography of one of the British Museum’s Jericho skulls, in addition to type faces selected create ancient historical resonance. I had extremely limited time to work on this weeks challenge, so I feel that the editorial design could be developed a lot further: specifically I would like to have isolated the skull image and explored how it could be used to interact more with typography and background texture to create a more compelling message for museum viewers.